Hope for water on Mars dries up:

Vast lake detected under the Red Planet’s south pole is likely just a dusty mirage, study claims

Hope of finding liquid water on Mars has dried up, according to scientists who predict what was thought to be a vast lake under the south pole is likely nothing more than a dusty mirage.

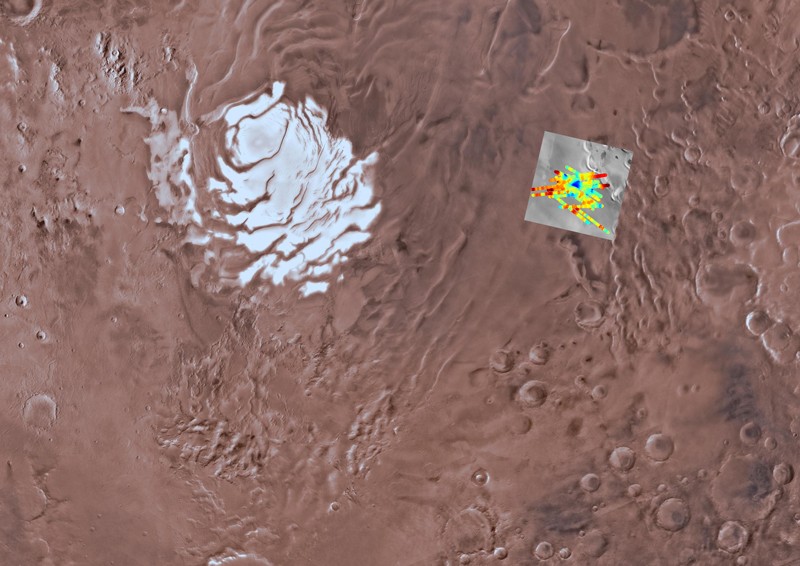

In 2018 scientists thought they were looking at liquid water on Mars, after seeing bright radar reflections under the polar ice cap, but a new study disputes that.

Re-examining the reflections in the radar images, planetary scientists from the University of Texas determined they were actually showing volcanic rock.

The NASA-funded study found that the reflections, seen shining through the ice, matched those of volcanic plains found all over the red planet’s surface.

This is a ‘more plausible explanation’ for the 2018 discovery than the Red Planet holding a vast lake, the authors said, adding that Mars is unlikely to have the conditions required to keep water in a liquid state at its cold, arid south pole.

The same team are now working on a proposed new mission to use radar to search for water on Mars, which could serve as a crucial a resource for future human landings.

Vast lake detected under the Red Planet’s south pole is likely just a dusty mirage, study claims

The south polar mirage, as the team have dubbed the phenomenon, was debunked when study author Cyril Grima added an imaginary global ice sheet across a radar map of Mars to see what could be seen in areas where the surface is visible.

‘For water to be sustained this close to the surface, you need both a very salty environment and a strong, locally generated heat source, but that doesn’t match what we know of this region,’ said Grima.

The imaginary ice sheet he placed over the planet showed how Mars’ terrains would appear when looked at through a mile of ice.

Doing so allowed them to compare features across the entire planet with those under the polar cap, and see if it matched any other region.

Grima noticed multiple reflections, like those at the south pole, but scattered across all latitudes of the Martian landscape, matching the locations of volcanic plains.

Iron-rich lava flows found on Earth can leave behind rock formations that reflect in radar images in a similar way to these plains on Mars, explained Grima.

He says this adds to the evidence that these volcanic formations sit under the Martian ice cap – not a liquid water lake.

Other possibilities include mineral deposits in dried riverbeds, and while not liquid water, figuring out the answer will ‘answer important questions about Mars’ history.’

The Red Planet is thought to have pockets of water ice, including at the thick polar ice caps, hinting at a wet past, and potentially providing support for future human habitation of the dead world.

Grima’s map is based on three years of data from MARSIS, a radar instrument launched in 2005 aboard the European Space Agency’s Mars Express that has accumulated tremendous amounts of information about Mars.

Isaac Smith, a Mars geophysicist at York University wasn’t involved in the study, but said the findings present ‘precise places’ to look for water ice.

He believes the bright radar signatures are a kind of clay made when rock erodes in water, inspired by Earth-based clay that reflect radar in a similar way.

‘I think the beauty of Grima’s finding is that while it knocks down the idea there might be liquid water under the planet’s south pole today,’ Smith explained.

He added it ‘gives us really precise places to go look for evidence of ancient lakes and riverbeds and test hypotheses about the wider drying out of Mars’ climate over billions of years.’

He says the study is a sobering lesson on the scientific process, showing that it is as relevant to studying Earth as it is to Mars, adding it ‘isn’t foolproof on the first try.’

‘That’s especially true in planetary science where we’re looking at places no one’s ever visited and relying on instruments that sense everything remotely,’ he added.

Grima and Smith are working together on a mission to find water on Mars with radar, both as a resource for future human landing sites and to search for signs of past life.

The findings have been published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Report by: Daliymail