There are many types of breast cancer, and many different ways to describe them. It’s easy to get confused.

A breast cancer’s type is determined by the specific cells in the breast that become cancer.

1. Ductal or lobular carcinoma breast cancers

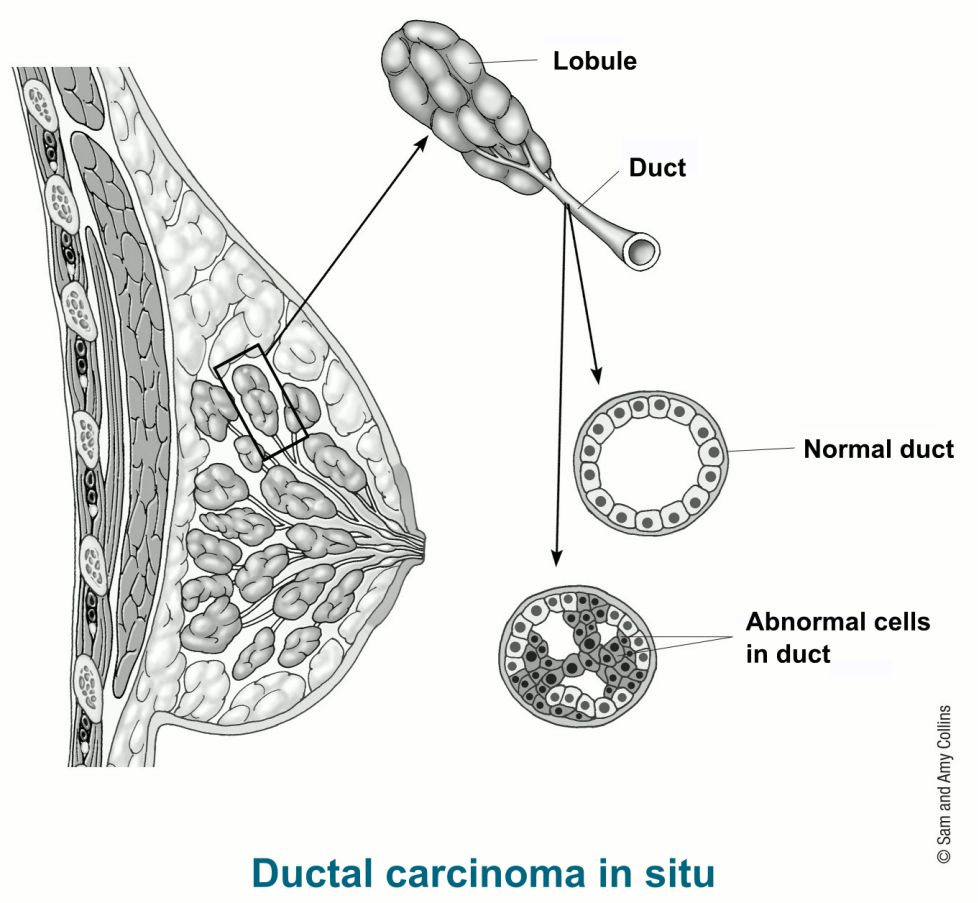

Most breast cancers are carcinomas, which are tumors that start in the epithelial cells that line organs and tissues throughout the body. When carcinomas form in the breast, they are usually a more specific type called adenocarcinoma, which starts in cells in the ducts (the milk ducts) or the lobules (glands in the breast that make milk).

In situ vs. invasive breast cancers

The type of breast cancer can also refer to whether the cancer has spread or not. In situ breast cancer (ductal carcinoma in situ or DCIS) is a pre-cancer that starts in a milk duct and has not grown into the rest of the breast tissue. The term invasive (or infiltrating) breast cancer is used to describe any type of breast cancer that has spread (invaded) into the surrounding breast tissue.

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS)

About 1 in 5 new breast cancers will be ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Nearly all women with this early stage of breast cancer can be cured.

DCIS is also called intraductal carcinoma or stage 0 breast cancer. DCIS is a non-invasive or pre-invasive breast cancer. This means the cells that line the ducts have changed to cancer cells but they have not spread through the walls of the ducts into the nearby breast tissue.

Because DCIS hasn’t spread into the breast tissue around it, it can’t spread (metastasize) beyond the breast to other parts of the body.

However, DCIS can sometimes become an invasive cancer. At that time, the cancer has spread out of the duct into nearby tissue, and from there, it could metastasize to other parts of the body.

Right now, there’s no good way to know for sure which will become invasive cancer and which ones won’t, so almost all women with DCIS will be treated.

Treating DCIS breast cancer

In most cases, a woman with DCIS can choose between breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and simple mastectomy. Radiation is usually given after BCS. Tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor after surgery might also be an option if the DCIS is hormone-receptor positive.

2. Invasive Breast Cancer (IDC/ILC)

Breast cancers that have spread into surrounding breast tissue are known as invasive breast cancers.

Most breast cancers are invasive, but there are different types of invasive breast cancer. The two most common are invasive ductal carcinoma and invasive lobular carcinoma.

Invasive (infiltrating) ductal carcinoma (IDC) breast cancer

This is the most common type of breast cancer. About 8 in 10 invasive breast cancers are invasive (or infiltrating) ductal carcinomas (IDC).

IDC starts in the cells that line a milk duct in the breast. From there, the cancer breaks through the wall of the duct, and grows into the nearby breast tissues. At this point, it may be able to spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body through the lymph system and bloodstream.

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) breast cancer

About 1 in 10 invasive breast cancers is an invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

ILC starts in the breast glands that make milk (lobules). Like IDC, it can spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body. Invasive lobular carcinoma may be harder to detect on physical exam and imaging, like mammograms, than invasive ductal carcinoma. And compared to other kinds of invasive carcinoma, it is more likely to affect both breasts. About 1 in 5 women with ILC might have cancer in both breasts at the time they are diagnosed.

Less common types of invasive breast cancer

There are some special types of breast cancer that are sub-types of invasive carcinoma. They are less common than the breast cancers named above and each typically make up fewer than 5% of all breast cancers. These are often named after features of the cancer cells, like the ways the cells are arranged.

Some of these may have a better prognosis than the more common IDC. These include:

- Adenoid cystic (or adenocystic) carcinoma

- Low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma (this is a type of metaplastic carcinoma)

- Medullary carcinoma

- Mucinous (or colloid) carcinoma

- Papillary carcinoma

- Tubular carcinoma

Some sub-types have the same or maybe worse prognoses than IDC. These include:

- Metaplastic carcinoma (most types, including spindle cell and squamous, except low grade adenosquamous carcinoma)

- Micropapillary carcinoma

- Mixed carcinoma (has features of both invasive ductal and invasive lobular)

In general, all of these sub-types are still treated like IDC.

Treating invasive breast cancer

Treatment of invasive breast cancer depends on how advanced the cancer is (the stage of the cancer) and other factors. Most women will have some type of surgery to remove the tumor. Depending on the type of breast cancer and how advanced it is, you might need other types of treatment as well, either before or after surgery, or sometimes both.

Special types of invasive breast cancers

Some invasive breast cancers have special features or develop in different ways that influence their treatment and outlook. These cancers are less common but can be more serious than other types of breast cancer.

3. Triple-negative Breast Cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for about 10-15% of all breast cancers. The term triple-negative breast cancer refers to the fact that the cancer cells don’t have estrogen or progesterone receptors (ER or PR) and also don’t make any or too much of the protein called HER2. (The cells test “negative” on all 3 tests.) These cancers tend to be more common in women younger than age 40, who are Black, or who have a BRCA1 mutation.

TNBC differs from other types of invasive breast cancer in that it tends to grow and spread faster, has fewer treatment options, and tends to have a worse prognosis (outcome).

Signs and symptoms of triple-negative breast cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer can have the same signs and symptoms as other common types of breast cancer.

How is triple-negative breast cancer diagnosed?

Once a breast cancer diagnosis has been made using imaging tests and a biopsy, the cancer cells will be checked for certain proteins. If the cells do not have estrogen or progesterone receptors (ER or PR), and also do not make any or too much of the HER2 protein, the cancer is considered to be triple-negative breast cancer.

Survival rates for triple-negative breast cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is considered an aggressive cancer because it grows quickly, is more likely to have spread at the time it’s found, and is more likely to come back after treatment than other types of breast cancer. The outlook is generally not as good as it is for other types of breast cancer.

Survival rates can give you an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful.

Keep in mind that survival rates are estimates and are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had a specific cancer, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. These statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk with your doctor about how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your situation.

What is a 5-year relative survival rate?

A relative survival rate compares women with the same type and stage of breast cancer to women in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of breast cancer is 90%, it means that women who have that cancer are, on average, about 90% as likely as women who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed.

Where do these numbers come from?

The American Cancer Society relies on information from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) database, maintained by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), to provide survival statistics for different types of cancer.

The SEER database tracks 5-year relative survival rates for breast cancer in the United States, based on how far the cancer has spread. The SEER database, however, does not group cancers by AJCC TNM stages (stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, etc.). Instead, it groups cancers into localized, regional, and distant stages:

- Localized: There is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the breast.

- Regional: The cancer has spread outside the breast to nearby structures or lymph nodes.

- Distant: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body such as the lungs, liver, or bones.

5-year relative survival rates for triple-negative breast cancer

These numbers are based on women diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer between 2011 and 2017.

| SEER Stage | 5-year Relative Survival Rate |

| Localized | 91% |

| Regional | 65% |

| Distant | 12% |

| All stages combined | 77% |

Understanding the numbers

- Women now being diagnosed with TNBC may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on women who were diagnosed and treated at least four to five years earlier.

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age, overall health, how well the cancer responds to treatment, tumor grade, and other factors can also affect your outlook.

Treating triple-negative breast cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer has fewer treatment options than other types of invasive breast cancer. This is because the cancer cells do not have the estrogen or progesterone receptors or enough of the HER2 protein to make hormone therapy or targeted HER2 drugs work. Because hormone therapy and anti-HER2 drugs are not choices for women with triple-negative breast cancer, chemotherapy is often used.

If the cancer has not spread to distant sites, surgery is an option. Chemotherapy might be given first to shrink a large tumor, followed by surgery. Chemotherapy is often recommended after surgery to reduce the chances of the cancer coming back. Radiation might also be an option depending on certain features of the tumor and the type of surgery you had.

In cases where the cancer has spread to other parts of the body (stage IV), platinum chemotherapy, targeted drugs like a PARP inhibitor, or antibody-drug conjugate, or immunotherapy with chemotherapy might be considered.

4. Inflammatory Breast Cancer

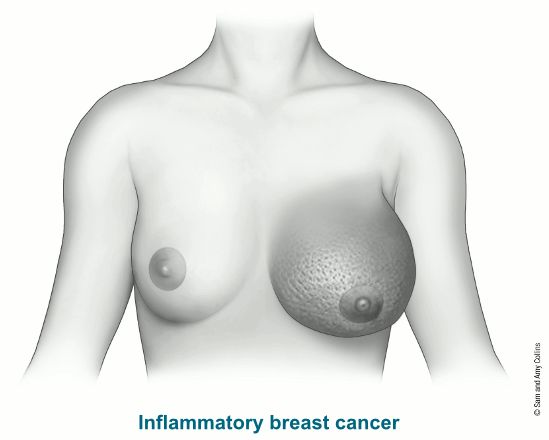

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is rare and accounts for only 1% to 5% of all breast cancers. Although it is a type of invasive ductal carcinoma, its symptoms, outlook, and treatment are different. IBC causes symptoms of breast inflammation like swelling and redness, which is caused by cancer cells blocking lymph vessels in the skin causing the breast to look “inflamed.”

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) differs from other types of breast cancer in many ways:

- IBC doesn’t look like a typical breast cancer. It often does not cause a breast lump, and it might not show up on a mammogram. This makes it harder to diagnose.

- IBC tends to occur in younger women (younger than 40 years of age).

- Black women appear to develop IBC more often than white women.

- IBC is more common among women who are overweight or obese.

- IBC tends to be more aggressive—it grows and spreads much more quickly—than more common types of breast cancer.

- IBC is always at a locally advanced stage when it’s first diagnosed because the breast cancer cells have grown into the skin. (This means it is at least stage III.)

- In about 1 of every 3 cases, IBC has already spread (metastasized) to distant parts of the body when it is diagnosed. This makes it harder to treat successfully.

- Women with IBC tend to have a worse prognosis (outcome) than women with other common types of breast cancer.

Signs and symptoms of inflammatory breast cancer

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) causes a number of signs and symptoms, most of which develop quickly (within 3-6 months), including:

- Swelling (edema) of the skin of the breast

- Redness involving more than one-third of the breast

- Pitting or thickening of the skin of the breast so that it may look and feel like an orange peel

- A retracted or inverted nipple

- One breast looking larger than the other because of swelling

- One breast feeling warmer and heavier than the other

- A breast that may be tender, painful or itchy

- Swelling of the lymph nodes under the arms or near the collarbone

If you have any of these symptoms, it does not mean that you have IBC, but you should see a doctor right away. Tenderness, redness, warmth, and itching are also common symptoms of a breast infection or inflammation, such as mastitis if you’re pregnant or breastfeeding. Because these problems are much more common than IBC, your doctor might suspect infection at first as a cause and treat you with antibiotics.

Treatment with antibiotics may be a good first step, but if your symptoms don’t get better in 7 to 10 days, more tests need to be done to look for cancer. Let your doctor know if it doesn’t help, especially if the symptoms get worse or the affected area gets larger. The possibility of IBC should be considered more strongly if you have these symptoms and are not pregnant or breastfeeding, or have been through menopause. Ask to see a specialist (like a breast surgeon) if you’re concerned.

IBC grows and spreads quickly, so the cancer may have already spread to nearby lymph nodes by the time symptoms are noticed. This spread can cause swollen lymph nodes under your arm or above your collar bone. If the diagnosis is delayed, the cancer can spread to distant sites.

Survival rates for inflammatory breast cancer

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is considered an aggressive cancer because it grows quickly, is more likely to have spread at the time it’s found, and is more likely to come back after treatment than other types of breast cancer. The outlook is generally not as good as it is for other types of breast cancer.

Survival rates can give you an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful.

Keep in mind that survival rates are estimates and are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had a specific cancer, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. These statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk with your doctor about how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your situation.

What is a 5-year relative survival rate?

A relative survival rate compares women with the same type and stage of breast cancer to women in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of breast cancer is 70%, it means that women who have that cancer are, on average, about 70% as likely as women who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed.

Where do these numbers come from?

The American Cancer Society relies on information from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, maintained by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), to provide survival statistics for different types of cancer.

The SEER database tracks 5-year relative survival rates for breast cancer in the United States, based on how far the cancer has spread. The SEER database, however, does not group cancers by AJCC TNM stages (stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, etc.). Instead, it groups cancers into localized, regional, and distant stages:

- Localized: There is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the breast.

- Regional: The cancer has spread outside the breast to nearby structures or lymph nodes.

- Distant: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body such as the lungs, liver or bones.

5-year relative survival rates for inflammatory breast cancer

These numbers are based on women diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer between 2011 and 2017.

(There is no localized SEER stage for IBC since it has already reached the skin when first diagnosed.)

| SEER Stage | 5-year Relative Survival Rate |

| Regional | 54% |

| Distant | 19% |

| All SEER Stages | 40% |

Understanding the numbers

- Women now being diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on women who were diagnosed and treated at least four to five years earlier.

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age, overall health, how well the cancer responds to treatment, tumor grade, and other factors can also affect your outlook.

Treating inflammatory breast cancer

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) that has not spread outside the breast is stage III. In most cases, treatment is chemotherapy first to try to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to remove the cancer. Radiation and often other treatments, like more chemotherapy or targeted drug therapy, are given after surgery. Because IBC is so aggressive, breast conserving surgery (lumpectomy) and sentinel lymph node biopsy are typically not part of the treatment.

IBC that has spread to other parts of the body (stage IV) may be treated with chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and/or targeted drugs.

Less common types of breast cancer

There are other types of breast cancers that start to grow in other types of cells in the breast. These cancers are much less common, and sometimes need different types of treatment.

5. Paget Disease of the Breast Cancer

Paget disease of the breast is a rare type of breast cancer involving the skin of the nipple and the areola (the dark circle around the nipple). Paget disease usually affects only one breast. In 80-90% of cases, it’s usually found along with either ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or infiltrating ductal carcinoma (invasive breast cancer).

Signs and symptoms of Paget disease of the breast

The skin of the nipple and areola often looks crusted, scaly, and red. There may be blood or yellow fluid coming out of the nipple. Sometimes the nipple looks flat or inverted. It also might burn or itch. Your doctor might try to treat this as eczema first, and if it does not improve, recommend a biopsy.

Treating Paget disease of the breast

Paget disease can be treated by removing the entire breast (mastectomy) or breast-conserving surgery (BCS) followed by whole-breast radiation therapy. If BCS is done, the entire nipple and areola area also needs to be removed. If invasive cancer is found, the lymph nodes under the arm will be checked for cancer.

If no lump is felt in the breast tissue, and your biopsy results show the cancer has not spread within the breast tissue, the outlook (prognosis) is excellent.

If the cancer has spread within the breast tissue (is invasive), the outlook is not as good, and the cancer will be staged and treated like any other invasive ductal carcinoma.

6. Angiosarcoma of the Breast Cancer

Angiosarcoma is a rare cancer that starts in the cells that line blood vessels or lymph vessels. Many times it’s a complication of previous radiation treatment to the breast. It can happen 8-10 years after getting radiation treatment to the breast.

Signs and symptoms of angiosarcoma

Angiosarcoma can cause skin changes like purple colored nodules and/or a lump in the breast. It can also occur in the affected arms of women with lymphedema, but this is not common. (Lymphedema is swelling that can develop after surgery or radiation therapy to treat breast cancer.)

Treating angiosarcoma breast cancer

Angiosarcomas tend to grow and spread quickly. Treatment usually includes surgery to remove the breast (mastectomy). The axillary lymph nodes are typically not removed. Radiation might be given in certain cases of angiosarcomas that are not related to prior breast radiation. For more information on sarcomas, see Soft Tissue Sarcoma.

7. Phyllodes Tumors of the Breast

Phyllodes tumors (or phylloides tumors) are rare breast tumors that start in the connective (stromal) tissue of the breast. They are not the same as breast cancer.

Phyllodes tumors are most common in women in their 40s, but women of any age can have them. Women with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (a rare, inherited genetic condition) have an increased risk for phyllodes tumors.

Phyllodes tumors are often divided into 3 groups, based on how they look under a microscope:

- Benign (non-cancerous) tumors account for more than half of all phyllodes tumors. These tumors are the least likely to grow quickly or to spread.

- Borderline tumors have features in between benign and malignant (cancerous) tumors.

- Malignant (cancerous) tumors account for about 1 in 4 phyllodes tumors. These tend to grow the fastest and are the most likely to spread or to come back after treatment.

How do phyllodes tumors affect your risk for breast cancer?

Having a phyllodes tumor does not affect your breast cancer risk. Still, you may be watched more closely and get regular imaging tests after treatment for a phyloodes tumor, because these tumors can sometimes come back after surgery.

Treatment of phyllodes tumors of breast cancer

Phyllodes tumors typically need to be removed completely with surgery.

If the tumor is found to be benign, an excisional biopsy might be all that is needed, as long as the tumor was removed completely.

If the tumor is borderline or malignant, a wider margin (area of normal tissue around the tumor) usually needs to be removed as well. This might be done with breast-conserving surgery (lumpectomy or partial mastectomy), in which part of the breast is removed. Or the entire breast might be removed with a mastectomy, especially if a margin of normal breast tissue can’t be taken out with breast-conserving surgery. Radiation therapy might be given to the area after surgery, especially if it’s not clear that all of the tumor was removed.

Malignant phyllodes tumors are different from the more common types of breast cancer. They are less likely to respond to some of the treatments commonly used for breast cancer, such as the hormone therapy or chemotherapy drugs normally used for breast cancer. Phyllodes tumors that have spread to other parts of the body are often treated more like sarcomas (soft-tissue cancers) than breast cancers.

Phyllodes tumors can sometimes come back in the same place. Because of this, close follow-up with frequent breast exams and imaging tests are usually recommended after treatment.